By Fabio Santos

This blog brings together eleven reviews about “This is not Africa. Unlearn what you have learned”, a temporary exhibition shown at ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum from March to October 2021. The reviews were written by Master students of “Main Themes in International and Global History”, a course offered by me at Aarhus University in Autumn 2021. By including a museum visit and the assignment to critically engage with the artworks and overall framing of the exhibition, I aimed at shifting the standard historical syllabus towards the interdisciplinary analysis of global arts.

In her famous TEDx talk from 2009 and throughout her literary works, Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie cautioned against “the danger of a single story”. One-sided and shortsighted narratives about entire countries, regions, and continents – including the people living in and moving through them – privileges generalization over nuanced differentiation and relation. This comes with momentous consequences, as highlighted by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: the single story about “Africa” – as poor, war-torn, and lacking artistic and intellectual fierceness, to name but a few standard misconceptions – has become so engrained in the longue durée of knowledge production within the self-proclaimed modern West that many find it hard to multiply the single story told about “Africa”.

Besides drawing attention to the recognition of heterogeneity, critical scholars, artists, and activists have pointed out the need to look at global and transregional entanglements, as today’s structures in different parts of the world have developed through mutual influence and should therefore be analyzed jointly. As forcefully argued by Kenyan writer Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor in a keynote lecture last year, describing these histories and legacies simply as “shared”, however, euphemizes interactions made under blatantly unequal conditions, flattens enduring hierarchies, and minimizes lasting traumas and ongoing structural inequalities.

Even if the curatorial team draws a connection to Star Wars rather the steadily growing debates and interventions countering the coloniality of power reproduced in cultural and scientific institutions, “This is not Africa” can be seen as part of this critical endeavor: unlearning the single story about Africa and instead focusing on the multiple stories told by artists from Africa(s) and the African diaspora(s).

Review written by Andreas Bennetzen Bierbaum

THIS IS NOT AFRICA – UNLEARN WHAT YOU HAVE LEARNED is a group of artist’s works exhibited at the Art museum of Aarhus, ARoS. The exhibition itself presents a wide variety of art by a total of twenty-six different contemporary artist, whom either has a relation to or is from the African continent. The exhibition seeks to disrupt the stereotypical, conventional view and the Western narrative of what it means to be African or the beliefs of the African continent in general. The exhibition and the artists attempt to deconstruct the current view of Africa as well as establish and furthermore attempts to create new standards of understanding Africanness through the artist’s art, whether it be videos, installations, paintings, sculptures, photos, or performance art, which are all examples from the vast variety and types of art from the exhibition running. But does the exhibition live up to its objective?

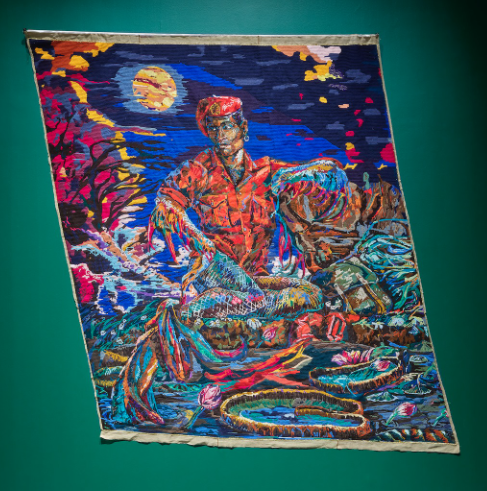

One of the installations on display at the THIS IS NOT AFRICA – UNLEARN WHAT YOU HAVE LEARNED exhibition is Inyanga yeDwarha (2021). Athi-Patra Ruga makes use of certain figures, he himself calls “avatars”, in order to process shifts in paradigms as well as trauma mainly focused on the African continent. The figures thereby, for Ruga himself becomes a way for him to explore the wounds within the societies and communities around him, as well as his own and perhaps the people who experience his art as well.

In the art piece Inyanga yeDwarha depicts the avatar Mayibue Kvesi, a mythological character who joins the army, however he ends up deeply traumatized, a process that divides his mind leading him to drowning himself as a result of the trauma and thereby turning him into a merman. In his work Ruga depicts Mayibue as a merman, wearing a military uniform with a resemblance to a lot of African military uniforms of the 1980’s and 1990’s, thereby creating his story as being relatively modern, for a mythological avatar.

Mayibue means “return the land”, as Ruga himself explains Mayibue Kvesi instead returns to water and becomes a merman, implying that he commits suicide by drowning himself. Ruga furthermore creates the narrative of the story of Mayibue Kvesi to be a mythological reenactment inspired by a series or spikes in suicide among soldiers subsequent to their return to their respective homes, from liberation battles and liberation struggles. Ruga tells from his own experiences as a child, that he was told to be aware of the mermen, the freedom fighters in post-apartheid South Africa who lost their minds and, in some cases also led to suicide. Which reflected upon can be a way for societies and communities to communicate trauma to children through storytelling, in this specific case of course being the urban mythology surrounding Mayibue.

Ruga thereby uses his avatars as a way to use mythology to criticize the status quo, as well as the historical past of Africa. His agenda becomes to have the audience put themselves, or at least for them to be represented by the art and African mythology. As well as a way to draw attention to the many freedom fighters who lost their minds in post-apartheid South Africa and the violent history of South Africa, which according to Ruga is still ongoing in present day.

The art piece by Ruga may seem very limited as it is just a depiction of the avatar Mayibue, however the story itself and the connection between mythological storytelling and the often-neglected violent history of South Africa, as Ruga points out himself in his interview and own description of his art becomes very apparent. However, the art piece does require the audience themselves to dwell into the story of Mayibue himself as well as the history of both apartheid and post-apartheid South Africa in order to create a connection between the artist’s intention and work. That being said, the case which Ruga displays through his art piece and mythological storytelling is a case which can be seen all over the world as a lot of societies has used the myths and storytelling as a way to describe the wrongdoings throughout their history.

THIS IS NOT AFRICA – UNLEARN WHAT YOU HAVE LEARNED as mentioned earlier is made up of a vast variety of art pieces by a numerous number of artists and therefore also various amounts of approaches to the objective of “unlearning what you have learned”. Ruga accomplished this through the installation of one his depictions of his mythological avatars, storytelling to create a stage for the history of a post-apartheid South Africa, however the art piece itself becomes for a reminder of the atrocities committed in South Africa. In my experience and exploring the art piece became more of a learning process of learning of the mythological and a reminder to look at both sides of history in order to understand how a nation as well as their people are affected from both internal and external factors. As for the entire exhibition itself, I felt that the pop culture reference from Star Wars and quote “Unlearned what you have learned” by Yoda from Star Wars to be unnecessary, as the concept of deconstructing and rethinking the Western narrative of Africanness would be a strong message even without this particular Star Wars reference as approach.

The entire objective of the exhibition is very apparent throughout the entirety of the art displayed at ARoS, however the pieces do require a lot of information in order to understand fully. However, this aspect is not necessarily negative as I think it allows for the audience to wonder and interpret the art themselves and thereafter research of their own. However, it does create a need for the art pieces at the exhibition to first be seen, and then unlearning or reminding process begins for the audience who are interested in unlearning through their own research of the African continent. Therefore, I believe that the objective of the exhibition has been fulfilled, as long as the exhibition succeeds or continues to create an interest within its audience and other recipients of these types of artwork exhibitions. Thereby starting their own unlearning of the Western, or their own narrative of Africa’s culture, population, history and Africanness.

Review written by Jonatan Bundgaard-Nielsen

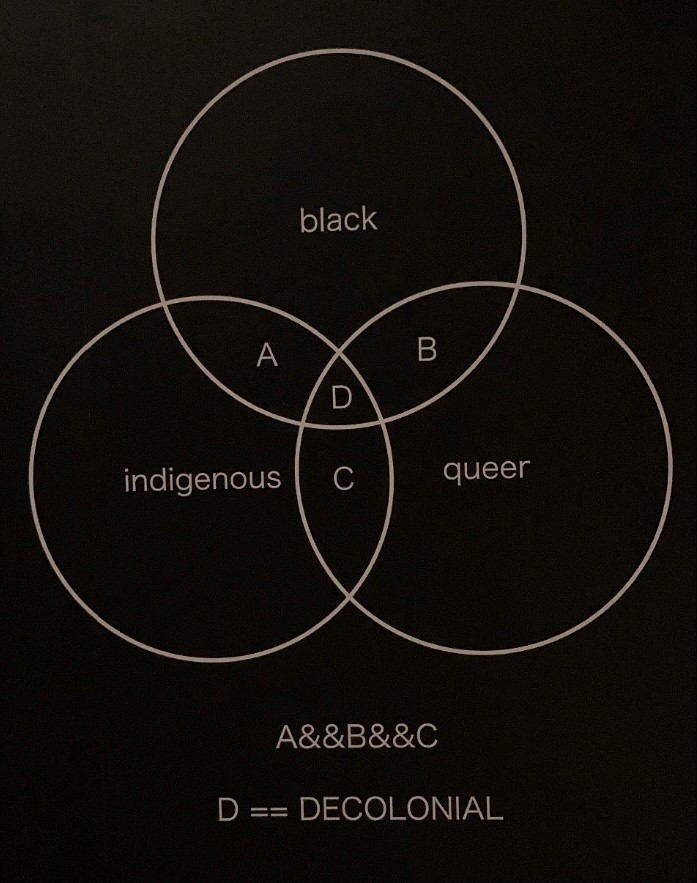

The exhibit containing the Inyanga yeDwarha piece is called “This is not Africa, unlearn what you have learned”, and is located at the ARoS art museum in Aarhus. The exhibit contains twenty-six pieces from artists from Africa or related diasporas and tackles the question of perceived African identities in a post-colonial world. Sometimes this is almost explicit, such as the case of the video piece Profile (2017) directly exploring South African identity of a broad range of people, and in different pieces this is much more subtle, such as a series of African masks made in the mold of the Guy Fawkes masks from the movie V for Vendetta. Concepts like decolonization, eurocentrism and racialization are an often-soft spoken undercurrent of the exhibit, and sometimes rather explicitly vocalized, such as in Nolan Oswald Dennis No Conciliation is Possible (2018), an installation where the artists attempts to spatially map out social constructions of language, order and understanding. In other pieces, the African experience frames other topics as well, including understanding of language, borders and structural racism.

The central theme of identity is critically assessed throughout the exhibit in many ways, but nowhere is the criticism of the sort of easily believed identities attributed to African peoples evident than in the title of the exhibit. It is a reminder that, while each voice represented in the exhibit certainly speaks to an African identity, no one piece can truly capture the enormity of expression in the decolonial African world. Each piece exists as an expression of a singular perspective within a larger narrative, reminding the visitor that a holistic perspective is nearly impossible. One piece that I have elected to highlight in particular is called Inyanga yeDwarha (2021), by South African artist Athi-Patra Ruga, depicting a character of modern South African folklore called Mayibuye, a phrase meaning “to come back”. It is a picture of a young, black man in military uniform sitting in a body of water facing the viewer. The water is filled with many almost fantastical plants, treasure chests, and rich colors. The man himself is transforming, his limbs taking on mer-like qualities like scales and caudal fins. His gaze is fixed to his right, where black shadows on a background of red appear almost as a forest on fire. In the story, Mayibuye is a young soldier who returns from war “split in mind”, and eventually drowns himself, unable to live with the trauma of his life, becoming a merman in death. The story is part of a larger South African narrative, in which the local traditions and story-telling practices are codified in a specifically African experience, called The Lunar Songbook. Mayibuye, for example, represents young South Africans who did actually commit suicide following their experiences in war.

I find it a moving depiction of a very specific, geographically isolated, social experience. Simultaneously, there are clear parallels in the piece to otherwise unrelated experiences across a rapidly decolonizing, war-torn continent. However, despite this, it is important to remember the limitations of the exhibit; no twenty-six piece exhibit could possibly tell the story of African identity. In this fashion, Inyanga yeDwarha accomplishes its purpose in the broader exhibit. It seems easy, almost inevitable, to draw parallels, but one story is not Africa. More broadly, I believe that in trying to provoke visitors to question their conceptions of Africa, the exhibit was largely successful. Making sure to highlight the diversity of African identity not only through the breadth of artists who participated, but also the huge variety of artistic styles utilizing both images, sculptures, digital art and conceptual deconstruction. At the same time, however, the exhibits focus on uprooting, or unlearning, the visitors' perceptions leave you feeling somewhat lost. You leave with a deep sense of questioning your own understanding, without a real narrative or conceptual replacement given by the exhibit. This issue is most clear when considering the staggering broadness of the topics broached by the exhibit, ranging from Tracy Thompsons Cascading Royal Cookies (2021) commenting on global food production and the interconnection of global systems, and the negative aftereffects of liberation explored in Flowers for Africa (2019) by Kapwani Kiwanga.

It definitely has the intended initial effect; to show the scope of individuality of the African diasporas, but it is difficult for a casual or one-time visitor to imagine any coherent narrative understanding. It is certainly possible that this is intended, however to my mind it made the overall experience hard to internalize.

Review written by Marcel Deckert

“This is not Africa” is a temporary art exhitbition at the ARoS museum for modern Art in Aarhus and consists of a number of artworks from all over Africa. The goal of this exhibition is to shift and “disrupt” the perception on Africa. Therefore, the exhibition features contemporary artworks, including installation art, video, sculpture, painting, performance art and photography, with the aim to parody, shatter, destruct and eventually build “alternative frames of understanding and modes of expression”. Additionally, the ARoS museum collaborated with the SCCA, Red Clay and Nkrumah Voll from Ghana in order to realise this Project. The exhibition tries to achieve their goals through “a vibrant and energetic manifestation flowing through the museum landscape and breaking down boundaries, both mental and physical”. It is further stated that a dominant paradigm provided by the exhibition was not the aim, but rather an open conversation of interpretation and perception, for it would contradict the message of the exhibition of unlearning dominant paradigms about Africa.

To start with “The Dictionary” you first have to enter a dark room which is separated from the open rest of the exhibition. In this room you see five walls in the shape of a half-octagon. The walls each own a specific term which is explained with definitions and interpretations, as it would be in a dictionary. These terms – denial, guilt, shame, recognition and reparation – are slowly projected onto the walls one after another. This not only makes it easier to reflect on the terms but also provides a different effect: because the terms are not presented all at once, it creates an order and the recipient finds him/herself on a tour through the meanings and connections of these terms. One can experience that it is not only a physical but also a mental tour through different stages of realisation of an unjust era, which is colonialism. This message applies to the individual recipient for him/herself, but also to society as a whole.

This experience is further strengthened by the set-up of this artwork. Due to the size of the room and the five walls in the shape of a half-octagon, the viewer can’t overview all five terms from one position or with one look. In order to read all terms, and therefore fully comprehend the artwork, he/she has to move him/herself. Viewers have to move on from their current point of view and take new perspectives, physically and metaphorically, to be able to understand colonialism (see Fig. 1-2). The author herself is rather focusing on the written words on the walls, which give her the power to tell the stories she wants to tell, to decide what will be read and breaking out of imposed silencing. Combining these two aspects, it creates a good example on how art can work as a mediator of political messages without losing its artistic onthology. The recipient, however, is not being ‘untold’ about Africa, since the interpretations above, are highly connected to the interpretation of an individual. The viewer definitely gets a certain impression, but whether this impression is according to an unlearning of Africa, is highly questionable and probably still rather positioned within the ‚learned frames of colonial thinking.

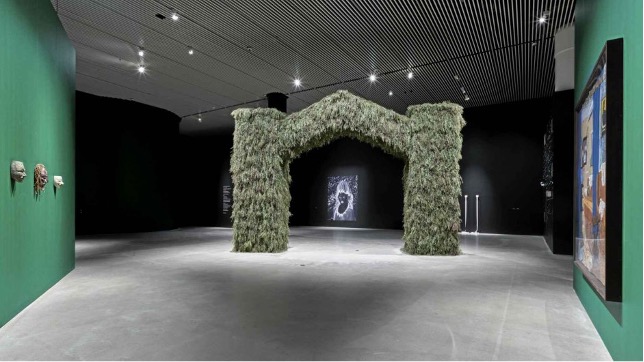

This is a problem which can be found throughout the whole exhibition and also in the next example “Flowers of Africa” by Kapwani Kiwanga. This monumental roomtaking plant-arch dominates the first hall of the exhibition. Besides its visual effect, however, it also creates a multisensory experience. The smell of the dried leaves of this arch can be perceived within the whole exhibition. It is also an ephemeric material which will change over time and at some point be gone. This effect is exactly the point made by the author. She wanted to present a state of expiry which resolves in a mulititude of perspectives because the subject is never in the same state. In my interpretation this artwork opens two additional aspects connected to ‘untelling Africa’: both the monumentality in the middle of the room, but also the fact that it is soon forgotten because information is rather scarce and difficult to catch, contribute towards the way we think about colonialism. Furthermore, it is the smell which creates a stereotypical atmosphere of an ‘African plane’ but only until you find out that the plants are actually eucalyptus, which originally comes from Australia. The stereotypical thought about Africa is actually rooted in something that is not even close of being African.

The examples have shown that the artists are very capable of presenting content that challenges the way of thinking about Africa in a subtle but still mildly shocking manner. They offer room for interpretation and deep reflection not only as artworks for themselves, but also the exhibition organised by ARoS for itself is neither crowded nor empty.

This room for interpretation is simultaneously the problem of the exhibition, though. It is shrinking the area of connection with the average recipient without an academic or differently special perspective. This is a basic problem with modern art and political messages. The danger is high that the recipient, even though aesthetically pleased, will not waste another thought about the connection to ‘untelling Africa’ which would resolve in a unaccomplished aim of the exhibition. Still, however, the concept of openness to interpretation can be very fruitful, because it further opens a multitude of perspectives. Maybe this multiperspectivity is exactly what is required in our view upon Africa. Recognizing that there isn’t one Africa but multiple versions of it.

A possible solution for this conflict of interests could be a higher density of information about intention of the artist in the direct vicinity of the artwork. This could help to provide first thoughts to the recipient, since the thought that one can transport political messages to a broader audience by “letting the Artwork speak for itself“ would, in my opinion, rather indicate an artistic ivory tower excused by room for multiperspectivity.

Review written by Rasmus Archard Heide

The following review of the This is not Africa exhibit might have a rather critical sentiment of the overall exhibit. This is a product of the rather limited possibility for expression given review size regulation. This review is therefore not meant as a representation of the exhibition but rather a critical discussion of its premise and one of the displayed artworks. Furthermore, I think it is important to note that this is a subjective viewpoint from an individual with a very limited connection and a low absorption level when it comes to the area of visual arts. While the exhibit did include a limited selection of art pieces which attained other senses, the primary expression was visual.

Firstly, a comment on the premise for the exhibit. It seems to me the premise has been to give African artist a chance to represent modern African art and give them a chance to set the stage themselves, rather than having some Europeans do an exhibit showcasing the everlasting archeological collection of masks and Sharman suits hoarded from the African continent. In itself the premise seems a rather brilliant idea, and surely genuine African culture represented by Africans themselves has been missing for decades from the mainstream art and historical museums in Denmark, of not most of Europe. It’s a rather refreshing chance of phase, and the representations debate is surely one deserving of more attention within the world of museums and art. It seems the post-colonial debate of identity and representation is allowing museums to showcase the other side of perspective on European/African relations and give a new insight into the representation of colonialism and its implications. However, one point in particular makes this entire premise almost a complete failure. The exhibit is curated by a European curator. It seems that no matter how hard the effort to let African culture express itself in a European institution, at the end there is always some kind of unnecessary “parental” supervision attached to the project, which I must say I thoroughly despise. What is the point of making space for African artist to express themselves and represent themselves if you are going to influence it with a non-African person anyway? However, I must confess that I am not aware to what point the curator has intervened in the overall expression of the exhibit. I am sure there is a reasoning behind it, rather it be limited resources or just convenience in staff already affiliated with the museum or to make the exhibit more easily accessible to the intended audience. This seems to me an enormous oversight at the very least and at the end, this European supervision seems to falsify the entire idea and premise behind the exhibition at which point it loses some of its meaning. This is, as the guide told us, why the “Not” was included in the title, but it seems to be misleading.

The art piece which I have chosen to focus on in this review also encapsulates this debate of representation or misrepresentation. It’s the work “V for Vendetta” created by white South African artist Dan Halter in 2015. Visually it contains six different variations of the Guy Fawkes mask featured in the comics by the same name as the artwork created by British author Alan Moores which was later adapted for screenplay. The mask in itself represents a homogenous social movement and a willingness to fight against fascist regimes. If this European symbolism of the mask is the core idea of the art piece, I must confess that I have misinterpreted the art piece. What seems to me to be the artist intention, however, is to use something most Europeans would see as the most iconic African artifact, the tribal masks, in an attempt to re-represent certain countries which five of the masks represent. I must confess I find this idea rather humorous and quite clever, as it seems to have quite the insight in what the European stereotype for African art looks like. This art piece plays perfectly into what most would imagine if you told them they were going to an exhibit on African art. I must point out, however, that this art piece exposes the same problems concerning (mis)representation. I am writing this without knowledge of the creation of the masks and whether Dan Halter sought cooperated with people from the countries he represents. I might point out that an issue of misrepresentation also might be the case with this art piece. As Dan Halter might possibly not be in a position to make assumptions on how five nations wish to be portrayed in masks. This might just be an indication that the problem of representation not only exists in the European/African reaction but also internally on the African and European continents.

Review written by Toke Kløve Junge

The mission statement of the exhibition “This is not Africa” at Aros in Aarhus, is spelled out in the subheading: “Unlearn what you have learned”. It is a deconstruction of prejudices about a heterogenous continent peopled by a sixth of the globe’s population. A noble goal, and one the exhibition tries to accomplish through “(…) a cacophonic array of different voices and forms of expression, testifying to the boundless complexity and diversity of Africa and the African diaspora.” 1 These voices are expressed through a collection of artists from different parts of the continent. Curiously the curators have chosen no artists from North Africa. Although inclusion of Imazighen or Arab-African experiences would have been welcome, it would have created a wholly different narrative.

The narratives presented, are therefore narratives of sub-Saharan or black Africa. These narratives are important to bring into public discourse, especially in Denmark where there are still debates about whether the use of the N-word, with all its connotations and stereotypes, is acceptable or not.2 But it is problematic, that five terms listed in a catalogue, are some of the only things the visitor really learns about a collective African experience. For an average visitor these five terms become a new foundation for ideas about Africa, and they are stretched a lot, to cover everything from the Cape to Cairo.

Despite this, the exhibition starts out with a strong message. One of the first pieces the visitor sees, is the Ethiopian artist Robel Temesgen’s “Adis Gazzetta”. A dualistic news-as-art project that has been running since, the Ethiopian government shut down six privately owned newspapers in 2014. The idea of presenting the audience head-on with an indigenous African writing system like ge’ez is a great decision, and one that undermines any idea of a primitive Africa”. Ethiopia is central to the imaginary of many in the African diaspora. Furthermore, Nelson Mandela described Ethiopia as “the birthplace of African nationalism”, the former emperor, Haile Selassie, is central to the diasporic religion of Rastafarianism, and the secretariat of the African Union is in Addis Ababa. This former empire plays a central part in the pan-African imaginary, and it is fitting, that a country that fits so little within the Western construct of Africa, should be so central, to an exhibition that deconstructs ideas about the continent. Temesgen’s ideas about translations being “(…) chain of

involvement locked through trust”,4 and that translations create an accumulation of knowledge is fascinating and speaks to the idea that even a failed translation, is something wholly unique.5 His idea of creating an intracultural trust between Amharic speakers, and others is a wholesome call towards understanding between the Ethiopian diaspora, and their surroundings. But the piece is also a haunting reminder of the fragility of the public sphere. Even a powerful symbol like the ge’ez script, can be used for political control through print media.

Another evocative piece with a focus on the written word, is Grada Kilomba’s “The Dictionary”. The piece plays out as five pages of a dictionary are slowly revealed, to the sounds of crickets. The pages spell out definitions, synonyms, and antonyms of five steps. These can be seen as a pathway, by which one can become conscious of the background to, and consequences of, racial violence. As the real process, the piece is a slow process, but it gives time for thoughts to fully manifest. The five steps Kilomba lines out – denial, guilt, shame, recognition, reparation – show an understanding of the psychological, and collective processes, that normalize racism. An idea that could easily end up feeling preachy, has in Kilomba’s hands become a moment of quiet reflection and introspection, about the spectres of racially based violence, and how the viewers themselves can work towards overcoming processes that normalize it. These steps are not an easy path to follow. Like the Slovenian sociologist Slavoj Žižek says, stepping out of the ideology we view the world through, is a painful experience.6 With the end of Apartheid, some think that equal judicial rights, create equal opportunities, and that we live in a global post-racial society. Realizing that the spectres of colonialism and racism lingers on in economic (in)opportunities, and global structural inequalities is a hurtful process. Realizing that you might unknowingly be a contributor to this racialised world order, can be even more hurtful. But it is a realization that we nonetheless still need to cope with, and to understand the complexities of. When you live in privilege, equality can easily feel like demotion. But the first step towards reconciliation and understanding might just be listening in quiet reflection, to something you can’t debate like Kilomba’s dictionary.

The exhibit achieves the goal of showing the heterogeneity of African societies, through a myriad of art. But this myriad entails a danger of it being jumbled together into something completely incoherent. That depends on the individual viewing the exhibit of course. Despite of this, I think the exhibit is a necessary addition to the Danish public consciousness of Africa. Showing the heterogeneity of the African experience and the individual creativity of African artists, is an important part of unlearning homogenized ideas of the continent. But learning about the continent anew, takes an effort by the visitor, an effort that I don’t think an art museum can be responsible for. It is important, that an exhibition about unlearning should awaken a curiosity about the continent, and a consciousness about what it isn’t. The exhibition achieves the latter, but falters at achieving the former. This is still commendable, and I hope that it can be part of a more nuanced debate about the role of Africa in the Danish conscious. One that doesn’t simply become another debate about the N-word.

[1] “This is not Africa” exhibition pamphlet

[2] Temi, Odumosu (2019) What Lies Unspoken, Third Text, 33:4-5, 618-623

[3] Mandela, Nelson (1995), The Long Walk to Freedom, Little, Brown and Company. Ch. 47

[4] “This is not Africa” exhibition pamphlet

[5] Moyn, S., & Sartori, A. (Eds.). (2013). Global Intellectual History. Columbia University Press. p. 11

[6] Fiennes, Sophie, James Wilson, and Slavoj Žižek. 2012. The pervert's guide to ideology. [New York]: Zeitgeist Films.

Review written by Kim Oliver Knappert

ARoS has had its fair share of thought-provoking exhibition over the years, and the current exhibition, called “this is not Africa”, is no exception. Although confusing, the concept of the exhibition is, that we as visitors are supposed to “unlearn what we have learned” about Africa. However, it is not able to provide us as visitors, a guide to how we are supposed to unlearn, as the exhibition does not educate the visitor further on the topic of Africa. This therefore poses the question to the visitors as ‘what Africa is then?’. There is a reason for this lack of information, it should also be noted. The curator for the exhibition, Maria Kappel Blegvad, claims that she is not able to justify how we are supposed to relearn Africa as a concept, seeing as she herself cannot arrange this exhibition in a way that makes it justified for the different African cultures, because she is not part of that culture.1 Although the exhibitions title causes some confusion, it does not harm the exhibition in itself , because as I stated, it is thought provoking.

The piece that caught my attention the most, was made by Meschac Gaba. He portrayed objects underneath a market stall with money on the top, whilst also hanging money off a metallic umbrella. Out of the 3 Stalls, the one that especially caught my attention was one with cotton, in contrast to the others with small objects or electronics. I was fascinated by it because I associated it with the cotton plantations and slavery in the southern U.S.A, that were caused by the transatlantic slave trade between Europa, Africa, and the United States of America. This production collapsed after the emancipation of the slaves that occurred in the wake of American Civil War. This destroyed parts of established trade routes between the U.S.A and Europe, thereby causing a “cotton famine”. This was a global shortage of cotton due to the European industrial nation’s dependency on the U.S. cotton production, which produced 97 % of the worlds raw cotton at the time.2 Through this association, I was able to make the connection between the other small object under the table, and this one. It was a statement about the continuous exploitation of Africa from the 15th century until today. The small gadgets and electronics, I presume, were placed here to showcase the Western world’s dependency on Africa’s rich mineral resources. The small Western buildings are probably there, to show how much European civilization and history, is built upon the exploitation of Africa, and how much the west still depends on it. This is shown through the use of both colonial era houses, and modern buildings.

Another more abstract train of thought that I had when studying this piece of art, was that the artist intended for us to see it as a tree with multiple layers. The first layer is the seed, which is shown through the bottom part of the market stall, or in this case Africa and its natural resources. The second part of the tree is above the ground, which is currency that has close to no worth because it has deflated in value. I saw this as an interpretation of Africa’s struggle to get a foothold into the capitalist world market, where even if a country can lift itself from the perspective of only being a resource depot, it cannot establish itself in this market as an equal partner in contrast to the rest of the world. The last piece of the tree is of course the crown, which I had anticipated would be staked with high value currency to show the difference in the world between the global south and global north. Whereas the Western world lives in the crown of the tree, the global south lives buried under it for nourishment, or has fallen from the tree, and now lives in the middle. But my interpretation of this changed, as the artist chose to also use devalued currency within the crown also. This changed my perspective. I still saw it as a tree, but a sickly and dying tree without leaves, seeing that the materials she chose for the piece, are metal and deflated currency, and the only thing that could grow from such a tree, would be worthless currency, showcasing the global south’s place in the world.

As a final remark I would once again argue that the exhibitions biggest issue is that its title is misleading. The different works included within it are interesting and stimulating to engage with, but it is hard to understand or think about the different works, when the title is not put into a context that works for the exhibition. I do not believe that it is about unlearning Africa but more about rethinking our approach to it, so we can break with the often-prevailing Eurocentric worldview.

[1] So I was told on my guided tour

[2] Beckert, Sven. 2004. “Emancipation and Empire: Reconstructing the Worldwide Web of Cotton

Production in the Age of the American Civil War.” The American Historical Review 109 (5): 1405–38.

Review written by Alexander Korup Matthiasen

The exhibit at ARoS art museum in Aarhus called “THIS IS NOT AFRICA – UNLEARN WHAT YOU HAVE LEARNED” is fundamentally about rethinking what we know about Africa as a continent. Following a guided tour through the exhibit with my university class, we were introduced to many of the different themes by the guide. Following a course on “unlearning” different parts of the world, it seemed like a natural follow-up to our curriculum. However, it did not manage to live up to this expectation.

The exhibit consists of about 25 art pieces, most of which are different kinds of sculptures with a few video installments. While some were more cryptic and not as straight forward as others, they generally tended to portray some different aspects of what the artists thought of as African. This included an art piece made of plastic garbage that had floated from Western Europe and ended up in the African coast, which definitely made an impact on a more climate-oriented level. The piece was made by Moffat Takadiwa and seemed to be one of the art pieces there with a more obvious meaning behind it – that being pollution from Western Europe that ends up in relatively poor areas like coastal West Africa. However, this does not necessarily represent a general tendency for just the limited areas in question. In particular, this art piece was made by the artist from trash collected from his local beach. The exhibition is about the African continent in general and not very specific areas, yet in terms of this geographical limitation the art installation ends up representing a relatively small area instead. Even if this is the intention, the only real takeaway one can get from this (and several of the other installations may I add) is a relatively local African one – or not related to Africa at all. For this reason, I want to critique the general presentation of the artists as limited in scope to something entirely different than what they are branded as representing.

Instead of actively representing what the title and description suggests (namely Africa as a continent and indicates people have to “unlearn” what they know about it) it ends up represent something else entirely. This art piece in particular represents my critique relatively well, as it says more about global environmental problems by representing a very specific case of the Northwestern world’s leftovers of different kinds consumption ends up in areas of Africa that are generally speaking not particularly well off instead.

Another piece was a large gate decorated fully in flowers that wilted throughout the time it was located at the exhibition at ARoS. This art piece was made by Kapwani Kiwanga. We were told by the guide that the artist reportedly had made it based on a metaphor of the flowers of the gate representing the democracies in Africa: Initially beautiful but needlessly wilting over time either way. Though this said, the pamphlet for the exhibition talks more about the withering of the celebration and mentions the independence of Rwanda. However, since the exhibit is based on the entire continent, this seems just as problematic as what we are attempting to supposedly “unlearn”. In this case, it looks like the artist is representing an idea about or a general critique of African societies, but that seems to be a general assumption that many people who may be ignorant of Africa and African states also hold. However, not all democracies in Africa are failed nor do all show signs of “wilting”. Besides the still somewhat European influenced state of South Africa and the North African countries (whose democracies could also be discussed in great detail), a handful of the sub-Saharan African states also have shown great promise on their democratic developments (relative to others). For example, Ghana is considered to be of relatively low corruption compared to other sub-Saharan African nations,1 as well as being a generally interesting place to study the entire democratic process in Africa as a case. For this reason, you can also find books on Ghana’s case specifically, that also don’t necessarily show the general idea of a wilting democracy in Africa.2

For this reason, the exhibit slightly comes off as either as uninformed as it seems to indicate the guests could be, or at least does not really represent what it seems to be claiming. It does show aspects of Africa that one might not necessarily think of, which is also part of the goal, but when even the guide starts out explaining what “unlearning” means. This was followed by a disclaimer, that the exhibition does not try to teach you about what Africa is, as opposed to what you had to unlearn before you came. Because of this, I don’t think the exhibition achieves what it set out to do, despite some thoughtful art installations.

To summarize, the exhibition has well-made art, the execution just seems to me to fall a bit short from the intention and what it brands itself as.

Review written by Henrik Mogensen Nielsen

From March to October 2021 the Museum ARoS in Aarhus displayed the exhibition THIS IS NOT AFRICA - Unlearn What You Have Learned, an exhibition, comprising 26 works featuring a number of leading contemporary African artists, curated by Erlend G. Høyersten, Museum Director of ARoS, Maria Kappel Blegvad, Curator at ARoS and co-curated by Ibrahim Mahama and Selom Kedjie. I went to the exhibition accompanied by my university class and a guide, set out to unlearn what we allegedly had, or rather should have learned about Africa.

Initially, the museum guide tells us that the exhibition's subtitle, unlearn what you have learned, is a reference to the Star Wars saga's tale of the young Luke Skywalker's rediscovery of “the Force”, the magical field of tension that surrounds the entire living galaxy. To be able to utilize and learn the power of the Force, the Jedi Master Yoda tells him to "unlearn what you have learned". It is thus a premise for Skywalker's desire to learn knowledge that he renounces conventional views, and with an open mind accesses new and different knowledge - if he wants to master the unseen and what is yet incomprehensible to him. The metaphor serves as a subtle reference to the museum visitor's, the exhibition's observer, who, like Skywalker, only can gain insight into the exhibition's narrative if the observer is willing to be told and confronted with the African object in a different angle, an object that has often been characterized by allegedly misleading and subjective narratives.

The exhibition consists of a series of works made by African artists, some of the works are more of a traditional artistic nature; murals, silk collages, statues, and wood carvings - other works, consisting of everything from momentary ornate constructions decorated with eucalyptus leaves, recycled mattresses as structed and build as a fence and various film-clips of a diverse portfolio, of South Africans contemplating and evaluating their individual and collective affiliation, for better or worse, to the South African nation.

The works of art testifies to the interpretations and narratives about Africa, if not the Africa that we - the outsiders e.g., the Europeans, the Whites, etc., are missing either the knowledge and understanding, or simply have not learned about.

One of the first works to be presented to visitors of the exhibition, is Zimbabwean Dan Halter's display of African mask called V for Vendetta, named after the same well-known Action Thriller from 2005. The artwork's focal point is revenge, as is the film adaptation of Alan Moore's post-apocalyptic cartoon. The five masks at display are a reference of archetypal African mask-types from different regions, including one in the style of a Malawi ebony mask; a beaded Cameroonian mask; a Benin bronze; a Ndebele mask and a mask from the Ivory Coast. With the artwork, Halter wants to invoke the feeling of revenge and retribution of Africans against their former colonial masters, by exhibiting how the West, in the name of tourism and capitalism, has hijacked the traditional African use of masks, for its own well-profiting gain. Halter states that, the Guy Fawkes mask, worn by the protagonist of the cartoon, and later films are to be seen as an allegorical image of oppression and a symbol of anti-capitalism.

I found it below interesting how, or rather why, that Halter considers the mask as a sign of anti-capitalism, as neither Alan Moore's narratives nor the current use of the mask by the hacker group Anonymous have a declared anti-capitalist goal. However, both, Moore and the hacker-group, have shown their clear opposition to authoritarian collectivist regimes, e.g., Putin's Russia, The Muslim Brotherhood of Egypt, The Church of Scientology, the Islamic State (ISIS), Communist China etc.

At the end of the guided tour, I could not help but feel, that the objects of the exhibition are somewhat very similar to the classic Star Wars-saga, a binary tale. Here the black racialized Africans is acting as the good rebels and noble Jedis of this “exhibition-saga”. In the other ring corner is found in a mix of capitalism, white people, racism, triangular trade, and Western colonization as the personification of the evil Galactic Empire.

What I find most interesting about the exhibition is that I find it incapable of achieving what it initially exhorts to produce - a kind of unity in the African narrative. The only unity found in the exhibition is one of criticism of capitalism, the West, and the Whites. The exhibition and several of the works are reproductions counterfactual mixes of what I have been led to believe was stereotyping European views, for which, have not had a common representation in the West since the 1990s. The works' critique of crony capitalism, colonialism and slavery is valid – but simply not up to date, and thus misplaced. I find the exhibition is more an artistic reproduction of already established worldviews, on one hand artistic pleasing, on the other hand relatively banal.

I was saddened by the banality of a majority of the works of arts, since it seems that the African artists, including the exhibition ARoS, are of the opinion that the African narrative only can be distinguished by an organized Western past, without room for the individual African man, woman etc. The exhibition opts out of the individual narrative, in favor of a collective narrative about the lives of Africans, which apparently only needs to – or can be - defined from a Western lens, or the remnants of past Western involvement on the African continent.

Review written by Marie Søndergaard Nielsen

The exhibition

Grada Kilomba has created the art installation ‘The Dictionary’ (2017), which is a part of the ‘This is not Africa’ exhibition at ARoS. The exhibition, with the subtitle ‘unlearn what you have learned’, wants to challenge the stereotypical Western narrative of Africa. Made as a cooperation between ARoS, in Aarhus, and SCCA and Red Clay in Ghana, the exhibition features a wide range of various art pieces, all made by people from the African continent or from persons connected to the different African diasporas around the world.

The artist

Grada Kilomba, born 1968 in Portugal, is an artist who focuses on memory, trauma, gender and post-colonialism, with the latter as the main focus for ‘The Dictionary’. Her art is often a mixture of text and picture, and the main object for her art is to, in her words, ‘decolonize the discourse’.

The art

The artwork consists of five dictionary entries that are projected on the walls, written in white on a black background. To see Kilomba’s piece of art you have to step away from the wide and tall rooms, which contain most of the exhibition, and into a smaller, darker room. Here the entries fill out all the space by itself, though the room is still connected to the rest of the exhibition by a wide opening. The room is sparsely lit, which makes the white text on the black wall stand out.

Denial, guilt, shame, recognition and reparation. According to Kilomba, the artwork came about as an answer to the question: ‘how is racialized violence normalized?’ . The text pieces itself are a collection of dictionaries that Kilomba studied in different languages and brought together in a new way, to which she also added some extra antonyms and synonyms. It is meant to show the different stages that you have to go through, to be aware of racism, as Kilomba puts it . I am not sure how she got to these five words and their specific order, but I definitely think they are relevant as a comment on racism and (de)colonisation. Many, if not all, who pass through the room and read Kilomba’s work will recognize some of the points made. Not as something abstract or unrelatable, but as something they can recognize. I think it is interesting to see the words put together, to see their definitions and to think of them as a connected thought process. The text is not accusing. It is simply there for everybody to read, so they can make their own sense of it.

Compared to the rest of the exhibition, ‘The Dictionary’ is at first glance a much more comprehensible, direct, and maybe even simple artwork. The dictionary entries are neatly presented on the wall, and there is nothing to distract you from taking your time to read through it all. For these reasons I noticed Kilomba’s work at first. It did not seem so abstract. It seemed to be pretty open about its message.

Review written by Sarah-Juliane Prey

The Exhibition “This Is Not Africa – Unlearn What You Have Learned”, displayed from March to October 2021 at the ARoS Museum in Aarhus, is a group exhibition created by 26 leading contemporary artists from or related to the African Continent. It presents a wide range of works, including installations, video works, sculptures, paintings, and photos as well as a performance programme, that try to challenge the stereotypes and biased Western views of Africa. The aim of the exhibition is to make the viewer question their relation of Africa and African cultures, going further, as to their perception of what Africa really is and isn't. The exhibition itself is not a Danish art project alone but a collaboration with the SCCA in Ghana, the exhibition is curated by Erlend G. Høyersten, Museum Director of ARoS and Maria Kappel Blegvad, Curator at ARoS. Both of them are Danish and not African so one could assume a dominant Western influence. With Ibrahim Mahama, Artist and Founder of the SCCA in Tamale and Selom Kudjie, Artistic Director of the SCCA, the curators took a huge step towards offering a new narrative and interpretation of the objects or materials displayed.

Located on the first floor of the museum, the entry of the exhibitions starts with Nastio Mosquito's video installation of “I am Jordan”. What you see is a video in which a man is giving a lecture. With this video, the artist sets the tone for the exhibition because one can only see a fragmented part of the lecture he’s giving. The artworks in the exhibition are at the same time only a fragmented narrative of what Africa is and isn’t. So, when going in, one should not expect to see a full picture of something so complex and large as Africa. Shortly after passing the video installation, a kind of dark hall offers a view on various artworks such as masks, a portal covered in eucalyptus and paintings. The overall mood is quite dark, with dark green and black walls behind the works. The exhibition hall is quite big, so each work is displayed in a distance from other works in order to allow the viewer to concentrate on its full potential without being distracted.

Participating artists among others are Barthélémy Toguo, Kelvin Haizel and others like Meschac Gaba and Moffat Takadiwa. This review will focus on the artworks of Barthélémy Toguo (Travel to Kochi) and Kelvin Haize (Ironing out difference). “Travel to Kochi” (2018) compromised thirteen large wooden busts that were designed to look like bureaucratic stamps. On those stamps are banners of various recent political protests around the world and popular slogans that trended on social media and elsewhere. When noticing how many stamps he already collected in his passport, Artist Toguo came up with “Travel to Kochi”. The stamps refer to the complex system of bureaucracy that travellers outside of the European Union/Schengen area have to go through when travelling. Travelling, including the form of migration, plays a huge role in sharing experiences and creating an identity. In addition, social media can change the perception of one's own identity. With the stamps, Toguo makes it visible how easy it is to be labeled by the act of stamping. Behind every stamp is so much more than just a word or a nation. It’s an individual with a history and by that means is Africa. “Traveling to Kochi” uncovers and represents the labels that Western society and politics placed on Africa and makes the viewer think of his/her own biased labels that he/she connects Africa with.

The second work is Kevin Haizels “Ironing out Difference”. Displayed in a separate smaller room, the viewer will see twenty-four ironing boards covered in canvas and bearing abstract brushstrokes. On top of that are orange picture planes with text written in Braille on them. On a huge table in front of the board is a light installation with light bulbs that light up from time to time. What one notices first when looking at the title is the pun, which was actually intended. Haizel got the idea when going to a local shop in Accra, Ghana, and seeing the retailers mix colours according to the specifications of the clients. From the wall where the newly mixed colours are tested, Haizels intention with his work was to give the opportunity to engage in a discourse of differences on both symbolic and material textures. What is so special about this work is that you have to first figure out what it's about and at the same time have an understanding of Braille in order to fully understand the meaning of the work. If you can't read the Braille on them, you don't understand what's going on. This was Haizel’s intention. The effort to learn the language in order to access what is referenced. It hints at the responsibility of learning as a necessary step of understanding and in particular, of understanding Africa. Language plays a huge role when it comes to understanding each other and new things. Language carries responsibility, experience and culture within it and is crucial how we talk about facts. It can shape a perspective and narrative that has influence on all of us.

Those two works and many others in this exhibition encourage us to rethink our narratives about Africa. About how we, not intentional, shape a narrative by what we say and sometimes what we don't say. We need to go beyond our biased vision of Africa and participate actively in greater self-insight. With his exhibition, a good starting point was set to engage with one very own perception about Africa. What needs to be criticized is the title of the exhibition. It’s the first thing a potential visitor engages with and the word ‘Unlearn’ is not doing justice to the exhibition's mission. Therefore, it should rather be a ‘rethink’ because before ones knows what to unlearn, one needs to be aware of what one has learned.

Review written by Eilef Refsnes

This compact review is based on own personal experiences and thoughts surrounding two separate art pieces from the “This is not Africa – unlearn what you have learned” exhibition at ARoS Art Museum in Aarhus, during a guided tour on Wednesday the 13th of October 2021. This specific exhibition contains art pieces from a total of 26 contemporary artists, which all are located from or have connections and/or relations to the African continent. The primary goal of the exhibition is to question the visitors on what is to be considered as “generally accepted knowledge and theories” surrounding the African continent. Key factors within the African continent in this setting includes such as the continents history, the cultural heritage, the people, and its representation, both in the past and our time. Throughout the exhibition it was primarily two art pieces, one in the form of a tapestry and the other as a direct object from the past, which stood out. The first piece is “Inyanga yeDwarha” by south-African artist Athi-Patra Ruga and the second one is “The hunting horn” by Congolese artist Sammy Baloji.

Both pieces will be examined and interpreted separately, after which they will be seen together with the main narrative of the exhibition.

First, it was the vibrant colours, especially the powerful red in the centre of the art piece which caught my eye. The diversity of colours popped out on the rather dark green wall behind. This was also partly because of the dimensions of the art piece, being rather large, taller than an average human. The piece is made from several different types of colourful fabrics, which together create a scene. In the centre of this scene is “the ocean man” Mayibuye, presented to us through a description of the artist himself. At first glance it seems to portray just a regular man in a striking red uniform, a soldier. On a closer inspection however, all is not as it seems. The soldier takes some sort of hybrid form. Much like the centaur, with the upper body of a human and the lower body of a horse, the lifeform of the waterman combines two parts of different species. With the upper body of a human and the lower body of some sort of fish-like creature, it seems fitting within the category of mythical creatures. Although my mind immediately jumped to pictures of mermaids or in this case a merman, the setting seems different. While merman and mermaids in the most classical sense are portrayed as vicious and cruel, the ocean man “Mayibuye” seem calm, friendly and at peace. Sitting calmly, glancing to the side, one hand supporting him on a rock, the other peacefully placed on his thigh, like he is resting. Surrounded by a bright full moon in the background, set in some sort of swamp, river, pond or similar water biome, the setting is beautiful from a purely landscape perspective. I gain a feeling of calmness when studying the art piece, not a feeling of conflict, as you might expect when looking at portrayed soldiers.

In one sense while the clearly physical trait, of the piece is appealing, it was first when I was greeted with the context and story behind the piece, that I really took the time to evaluate it in depth. The story behind the art piece present itself as strong contrast compared to its beautiful visuals. Not ugly, but tragic is the right word to sum up the story behind the art piece, presented to us by the artist. The emotionality and complexity of the history surrounding South-Africa is intriguing and creates good values for post-evaluation regarding this specific piece.

A thing of beauty is the first thought that comes to mind when seeing the golden hunting horn. Displayed all alone in a glass display, the golden metal shines towards you in the otherwise dark room. Double tubes and a series of meticulous placed dimples who form a series of patterns at the outlet of the instrument, all contributes to it being aesthetically pleasing to look at. The horn is in many ways a very direct materialistic piece from the colonial past, brought forward in the form of a collage of items from the Congolese artist Sammy Baloji. Mentioning the nationality in this context is of outmost importance, as the dimple patterns on the horn also is of traditional Congolese scarification. Mr Baloji also informs about the important metaphorical meaning of the piece through his own personal description of the art piece. As the hunting horn could represent the Western powers hunt for new land, territories, resources, and wealth in pursuing their imperialistic goals. In many ways this piece requires above average knowledge to grasp and understand all the different factors surrounding its meaning and symbolism. Certainly, a risk by the artist to expect and challenge the knowledge of the general public to such a high degree surrounding the main theme.

While I fully understand the goals that the “This is not Africa” exhibition aims to achieve, it presents itself problematic to conclude this goal is successfully achieved. Certainly, some art pieces in the exhibition achieve this better than others. Although this is by a large up to the viewers subjective interpretation of each piece, I personally think pieces with direct connection and relation to the colonial past with inherent stories and according contexts, more clearly get the goals and message across from the artist to the average visitor.

There is also some doubt surrounding the “unlearning what you have learned” as the key sentence for the interpretation of the exhibition. Although there without a doubt exist a lot of different skewed, misleading, or just plain wrong understanding and interpretations surrounding the African continent, its history, and culture both within and outside Western nations, I interpret this statement as a bit generalizing and condescending regarding the knowledge possessed by the general public. Key concepts and terms of the exhibition, such as decolonization, white supremacy and eurocentrism are well established at least with individuals of higher education and within academic circles environments.